A Month of Experimenting with Code and an Icon

For years, I've been obsessed with the Mona Lisa. My Daily Mona Lisa series on Instagram, with over 1000 entries, is a testament to that. But they've almost all been made manually with digital tools, commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) applications. As a professional programmer who also creates art, I wanted to more deeply integrate these two passions.

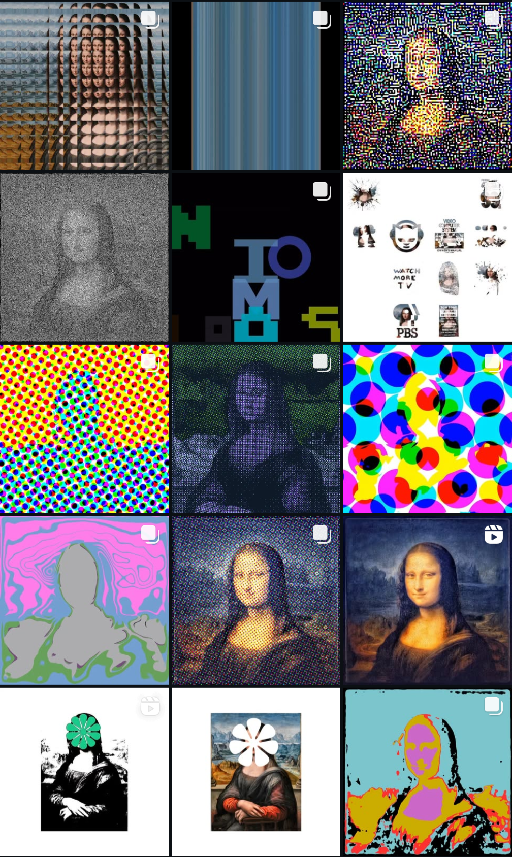

The concept was straightforward, though the execution was anything but: for one month, from January 3rd (when I realized I wasn't going to do Genuary) to February 3rd, 2025, I would create a new, code-generated variation of the Mona Lisa every single day. This wasn't about manipulating images in existing software; it was about writing code to generate something new each day. I'll be honest - my threshold for "new" was quite low - basically, anything other than the original Mona Lisa. But this wasn't about creating a masterpiece every day; it was about getting past an artistic and professional block.

Why the Mona Lisa?

The Mona Lisa's ubiquity is precisely what makes it such a compelling subject. It's an image so deeply embedded in our collective consciousness that it transcends being just a painting. It's a cultural touchstone, a visual shorthand that everyone recognizes. I wanted to use that familiarity as a foundation for exploration, a recognizable scaffold on which to build something new. And as a daily exercise, I can't fall back on "I don't know what to create today."

I've also long been inspired by artists like Andy Warhol, who explored the power of repetition and variation. I wanted to see if I could achieve a similar effect, but using code as my primary tool. The challenge, of course, is that coded images tend toward precision and uniformity. How could I introduce a sense of organic variation into a process that's inherently digital? I don't think I achieved any of that goal, but it was in the back of my mind throughout.

Code as a Creative Tool

P5.js (a JavaScript library for creative coding) is my primary visual code framework, and my first project was very simple - a single color-channel offset. The next day, I iterated by animating the offset. And then I kept going trying other things. One day I was starting close to midnight, so I placed a single asterisk over Mona Lisa's face. The next day, I iterated by making the asterisk draggable and other features. So even really simple last-minute code paid-off by suggesting more-complicated code down the road.

I also finally took the plunge into the world of shaders (GPU-based rendering, often used for games, that is blazingly fast). I had never worked with shaders before, but I had a few tutorials bookmarked, and a project I admired used them. I began by adapting existing code to remap the Mona Lisa's colors to a limited palette. From there, I started adding user interface (UI) controls to allow for real-time adjustments and variations.

As the month progressed, I explored other techniques, including color halftones and animation through gradual parameter changes. It was a great playground for digital experimentation.

The Daily Process and the Value of Experimentation

The daily pace of this project was demanding. Every day, I had to generate new code and a new visual output. Some days, I was building on previous code, adding new parameters or UI controls. Other days, I was starting from scratch. And, as with any experimental process, not everything was a success. Some of the visual effects were more compelling than others. But even the "failures" were valuable, as they often pushed me in new and unexpected directions.

Ultimately, this project was not about creating aesthetically pleasing images. Many of them were not -- they were images, but not aesthetically pleasing. It was about learning new techniques, pushing my own creative boundaries, and further exploring code as a creative tool. It was about embracing the experimental process and seeing where it would lead.

The Role of AI Assistance

One of the most interesting aspects of this project was my use of AI coding tools like Microsoft CoPilot, ChatGPT, and Amazon Q (I did not use Claude or Gemini at that time). This wasn't a case of "vibe coding," where AI generates the entire solution. I remained the primary author, using these tools as collaborative assistants.

These AI tools proved helpful for generating boilerplate code, refactoring, and helping me navigate technical challenges.

They gave me several user interface variations that I wouldn't have thought of on my own. I've mostly used dedicated UI libraries in the past, but I found that dead-simple interfaces looked decent and were easy to implement. For example, I created a simple slider to adjust parameters like color or offset, which allowed for real-time experimentation with the visual output.

The process of explaining coding concepts to an AI often required a precision that forced me to clarify and refine my own thinking.

And while the AI tools were not perfect —- they sometimes got stuck in loops or suggested non-working solutions -— they often led me down unexpected paths and sparked new ideas. It was a learning experience, both in terms of coding and in terms of working with AI. I did find it frustrating that various agents would quickly agree that I was correct when my understanding was wrong, but that's a different issue (and is also tied up with these being Large Language Models that neither think nor understand).

Looking Ahead

This project was a good step in merging my coding and artistic practices. This write-up is part of the follow-through, as will moving the code online. I'm hoping to do more code weekly or monthly, but I haven't yet. Worst-case scenario, it'll be another January project next year.

Available Code

Remember, these were created rapidly, if iteratively. My concern was creating code, generating an image, and preserving the code on either editor.p5js.org or in GitHub. Documentation and organization efforts were almost nil.